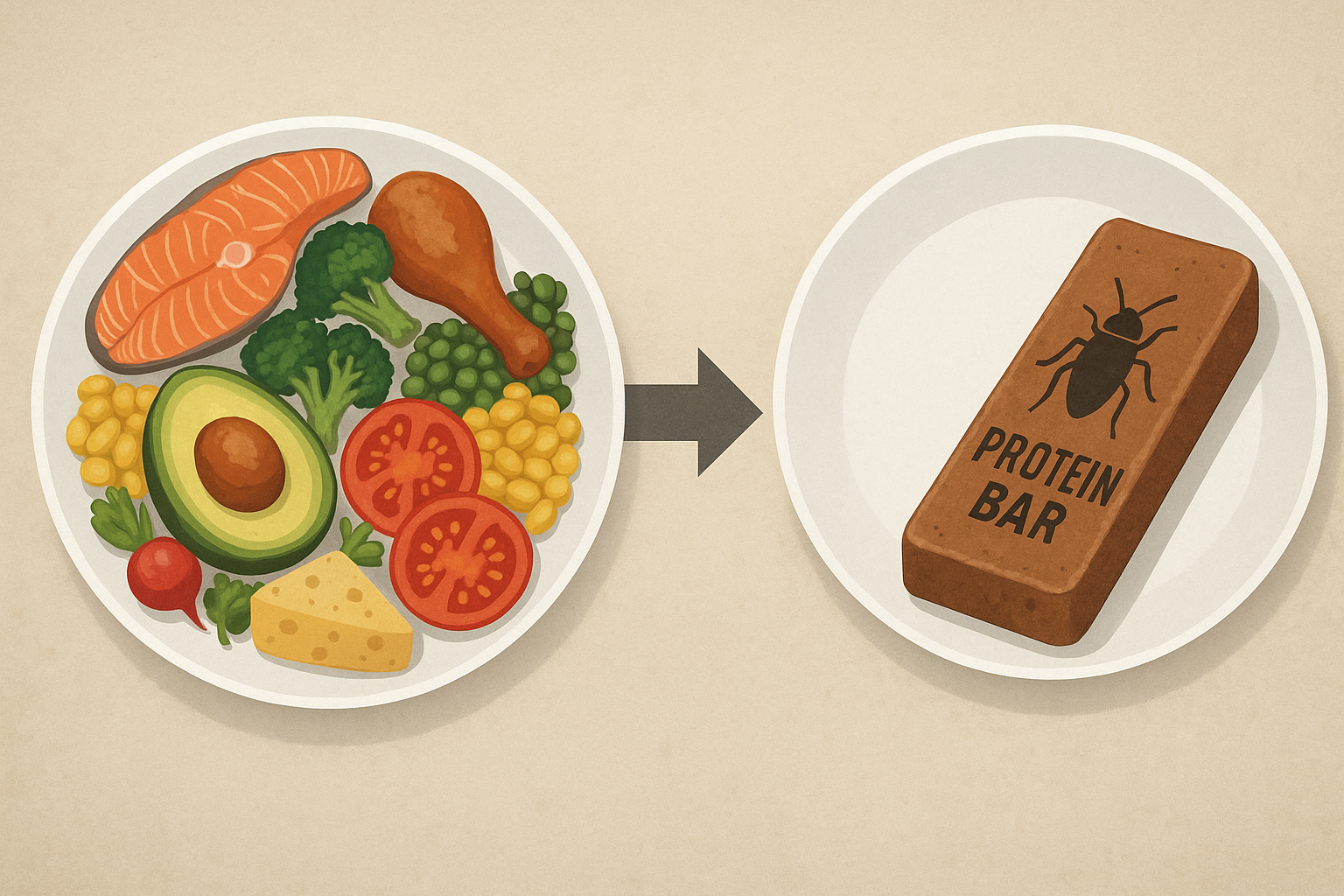

Modern food production is impressively efficient but increasingly homogenous, narrowing our dependence to a few hyper-productive species. This post reframes genetic diversity as a non-renewable resource, invoking economic ideas like Hotelling’s rule and Nordhaus’s backstop technology to argue that biodiversity loss behaves like the depletion of a strategic asset. Historical cases like the banana, citrus, and wheat industries show how producers often abandon at-risk lineages rather than coordinate costly solutions, accelerating genetic erosion. I explore a hypothetical market where biodiversity accrues scarcity rents, suggesting that only when diversity is valued like capital (rather than heritage) can we avoid locking ourselves into fragile, uniform food systems. But even then, efficiency does not guarantee equity, i.e., scarcity rents could conserve biodiversity while making good food unaffordable to most, leaving cockroach protein bars not as a collapse scenario, but as a logical outcome of market inequality.

In the first part of this post, I wrote about the efficiency of modern food production. We also noted its shadow: a creeping uniformity, a path dependence that locks us into a handful of hyper‑productive species. I have to recognize though, that this path dependence story wasn’t explained well enough; maybe I will work on this explanation in a later post.

It would be easy to take this observation (of path dependence and lock in situation) down a dark road. My professional de-formation as a natural resource economist often pushes me toward scarcity narratives. After writing the first part, I realized how quickly the story could become Malthusian, i.e., the grim prediction that population inevitably outstrips food supply. Yet that view discounts humanity’s remarkable ability to innovate precisely when scarcity bites. Scarcity is rarely the endpoint; more often, it is the trigger that unleashes entirely new ways of producing what we need (I realize after finishing the post, that reads even more pessimistic than the first one; perhaps the problem is a personality trait of the writer).

This capacity for reinvention is not merely theoretical, it is embedded in how resource use decisions unfold over time. Economists have formalized this through models like the Hotelling rule, which prescribes how exhaustible resources should ideally be consumed over time to balance present use with future scarcity, and Nordhaus’s backstop framework (Nordhaus, Houthakker, and Solow 1973), which describes how rising scarcity or costs can make alternative technologies viable.

Consider salmon aquaculture. Sixty years ago, launching a large‑scale salmon farm would have made little sense. Wild salmon were plentiful and inexpensive; the market for farmed fish was relatively small. However, as wild stock prices declined and demand increased, the economics shifted. We crossed a switch point, and today, farmed salmon is a multi‑billion‑dollar industry.This dynamic is a textbook example of Nordhaus’s “back‑stop technology” concept: once a cheap, finite resource runs short and its price rises, a more expensive but inexhaustible substitute becomes viable.

Just as farmed salmon became viable only when wild stocks decreased, future food sources may depend on whether we preserve (or waste) our biological options today.

Could our food system operate in a similar manner more broadly? When scarcity squeezes a staple crop, making it costlier or riskier, will we simply “switch on” a new food source from the planet’s biological library? What if, when that day comes, the library shelves are already bare? Will we end up eating cockroach protein bars as in Bong Joon‑ho’s Snowpiercer movie, where the tail section of the train survives on cockroach protein bars?

Diversity as a non-renewable resource

Stalker, Warburton, and Harlan (2021) documented that during earlier periods, particularly among pre-agricultural societies, more than 1,400 wild food species were used in sub‑Saharan Africa alone. FAO food‑balance sheets show that>50% of global calories now come from just three crops, i.e., wheat, rice, and maize, and another four species supply most of the rest. Diversity has already collapsed by over an order of magnitude.

For the argument that follows, let us assume that on a human timescale, edible diversity is a non-renewable resource. Evolution may replenish this stock over geological epochs, but not, I believe, within the lifetime of our civilization. Losing a species (or even a genetic lineage within one) is therefore an irreversible depletion of a finite asset. Of course, one could imagine some alternatives, such as humans evolving to live on air, a single strand of wheat providing complete nutrition, or aliens arriving with a galactic seed vault. But if that does not happen, and without abandoning major staples like wheat or beef, we are already surrendering irreplaceable versions of them. The Cavendish banana1 monoculture (Ploetz 2015), the decline of traditional poultry breeds, and the narrowing genetic base of global cattle herds FAO (2019) all demonstrate how quietly (and permanently) our options can disappear.

1 2 of the 50 subgroups of banana account for 64% of all production

Agricultural diversity, then, behaves like a non-renewable strategic asset. So what? Why is this guy putting so much effort into treating edible diversity as a non-renewable resource? Well, I think we can apply the well-known Hotelling rule to explain, predict, or simply consider grim futures (which I like to do).

What is the Hotelling rule? Put simply, when a resource cannot be replaced, every unit left in the ground (or gene bank) gains value over time (like money earning interest) because using it today leaves less for tomorrow. If markets felt that built‑in “scarcity interest,” society would draw down the stock more slowly and spread use across generations. The problem is that market forces will continue to deplete it because its Hotelling scarcity rent (the premium that should rise as an exhaustible resource declines) is largely invisible to individual producers. This cost is spread thinly across society and is only realized when systemic risk materializes.

By contrast, the private gains from specializing in a profitable monoculture are immediate, certain, and easily captured. When the scarcity rent remains external to farm-gate decisions, genetic erosion proceeds at a faster rate than the socially optimal path, leaving society with fewer options than economic efficiency would dictate.

This pattern of “abandon and replace” is well-documented in agricultural history and crop breeding research. The agronomic convenience of monocultures makes them the short-run winner (uniform sowing rates, a single input schedule, one machine fleet). Yet, this standardization also synchronizes risk, resulting in “boom and bust” cycles for many crops. A classic example is the Gros Michel banana, nearly wiped out by Panama Disease (Fusarium oxysporum Tropical Race 1) in the mid-20th century, and replaced by the Cavendish cultivar, which is now itself threatened by Tropical Race 4 (TR4) (Ploetz 2015). Similarly, when citrus greening (Huanglongbing) affected Florida’s citrus industry, producers essentially chose to abandon susceptible varieties rather than pay for costly landscape-level management whose benefits would benefit others (Singerman, Lence, and Useche 2017; Farnsworth et al. 2014). Wheat breeding also illustrates this dynamic: the emergence of the Ug99 strain of wheat stem rust has triggered ongoing breeding programs to repeatedly shift genetic resistance, exemplifying the recurring nature of genetic erosion and replacement (Singh et al. 2011). Each time an epidemic surfaces, the cheapest private response, i.e., abandoning the affected genetic lineage and shifting to a new, resistant variant, quietly erodes our global genetic reservoir.

What if, instead, we consider the scarcity rents of genetic loss?

Suppose there existed a market that priced genetic diversity like oil, where each genetic lineage, crop variety, or animal breed accrued scarcity rent as it became rarer. In such a world, the act of conserving biodiversity would carry an immediate financial reward, and the irreversible loss of a lineage would be seen not just as an ecological tragedy but an economic misstep. Gene banks would function like strategic petroleum reserves. Futures markets could emerge for crop traits such as drought resistance or disease tolerance, allowing for hedging against biological risks. The rising price of a depleting genetic option would signal its growing strategic value, influencing farm-level decisions, public investment, and long-term planning. In this framework, conservation would no longer need to rely on sentiment, regulation, or philanthropy. It would be driven by the cold, rational calculus of intertemporal asset management, a revaluation of biodiversity as capital, not just heritage.

Biodiversity plays the role of the option set of future back‑stops: each crop or genetic lineage we still possess is a latent technology whose fixed cost of adoption has already been paid by evolution and traditional knowledge. Squandering that option set now means the future switch point could arrive with no affordable substitute left (no shelf to switch to) making systemic failure the default rather than the worst‑case scenario.

Even if markets recognize biodiversity’s value, that doesn’t guarantee access. Scarcity rents might conserve diversity, but they could also concentrate it.

If these scarcity rents were to exist and guide our choices, would we still end up eating cockroach protein bars?

I think the answer is yes: Scarcity rents may make biodiversity legible to markets, but they won’t necessarily make it accessible to all (there is nothing in economic efficiency that takes into account distributional things). If prices reflect true scarcity and humans remain shortsighted, then prices for “good food” could become so high that the majority are priced out. The most diverse, nutritious, and culturally significant foods could become luxury goods, while the masses are left with whatever backstop technology remains. Cockroach bars not by necessity of collapse, but by logic of inequality.