Global food production has grown remarkably since the 1960s, not by expanding farmland, but through technological intensification of agricultural practices. Mechanization, synthetic inputs, and genetic selection have increased yields on land and in water. However, this success has come alongside a quiet trend: we are increasingly relying on a shrinking set of species to feed the world. In this post, I speculate that economic incentives and ease of domestication have gradually locked us into a path where diversity is traded for efficiency. This path-dependent process may constrain the resilience of future food systems in ways that are not yet fully visible.

Allow me to explore opinion fiction. One might ask: What is opinion fiction, and does such a thing even exist? Opinion and fiction must be closely related, regardless of whether the opinion holds any truth. I would argue, though, that opinion fiction must be treated with far more caution than regular opinion. Yet I would also say that opinion fiction proves more honest than expert opinion.

Why? Because expert opinion is masked with a royal cape that makes the listener hear something stripped of means to refute it, i.e., that opinion arrives bearing something akin to truth through its claim to expertise. But no one asks where your expertise comes from.

The fact

Since 1961, the average global food supply has increased from about 2,200 to nearly 3,000 calories per person per day. These impressive numbers do not mean that all people on the planet have that amount of calories available; we all know that is not true at all! Even so, the trend is striking: while the global population has more than tripled over this period, the amount of food produced has grown even faster. This expansion is not simply a story of feeding more mouths; it’s a story of unprecedented gains in productivity. The natural question that follows is: how was this achieved?

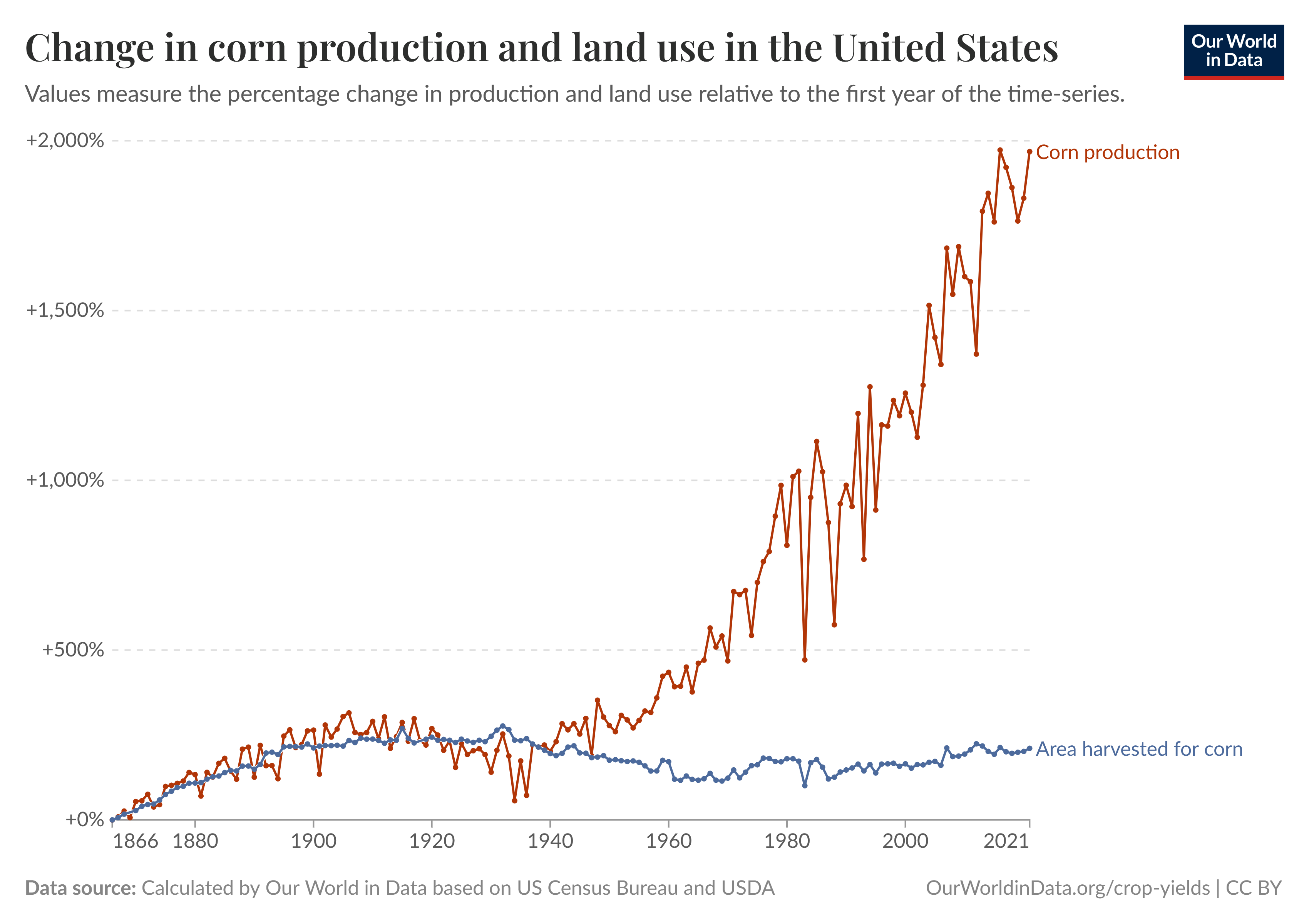

Of course, I won’t delve into the details of this agricultural revolution (that would require a book, not a blog post, and I’m not that well-versed in agricultural history). However, the short version is as follows: yields increased not because we farmed more land, but because we farmed it more intensively. New seed varieties, synthetic fertilizers, pesticides, and irrigation systems all played a role. Mechanization replaced manual labor in many regions, and farms grew larger and more specialized. In the U.S., for example, corn production has risen nearly twentyfold over the past century, yet the total land used for corn has remained roughly the same (Ritchie, Rosado, and Roser 2023). This means we learned to produce far more from the same soil. As shown in Figure 1, the gains in output vastly outpaced any increase in land use.

This transformation is also evident in the way agriculture is practiced. Figure 2 illustrates a century of mechanization, from hand harvesting and mule-powered threshers to modern combine fleets. Fewer people now harvest more food, more quickly, on more standardized fields.

The water saw a similar story. Aquaculture, once a minor contributor to the global food supply, has become the fastest-growing food production sector. Since 1990, global aquaculture production of aquatic animals rose from around 13 million to over 80 million metric tons, driven by new feed technologies, breeding programs, and a shift toward intensive farming systems. A recent study found that a 1% increase in domestic aquaculture production is associated with a 0.9% increase in national per-capita aquatic food consumption (Garlock et al. 2022).

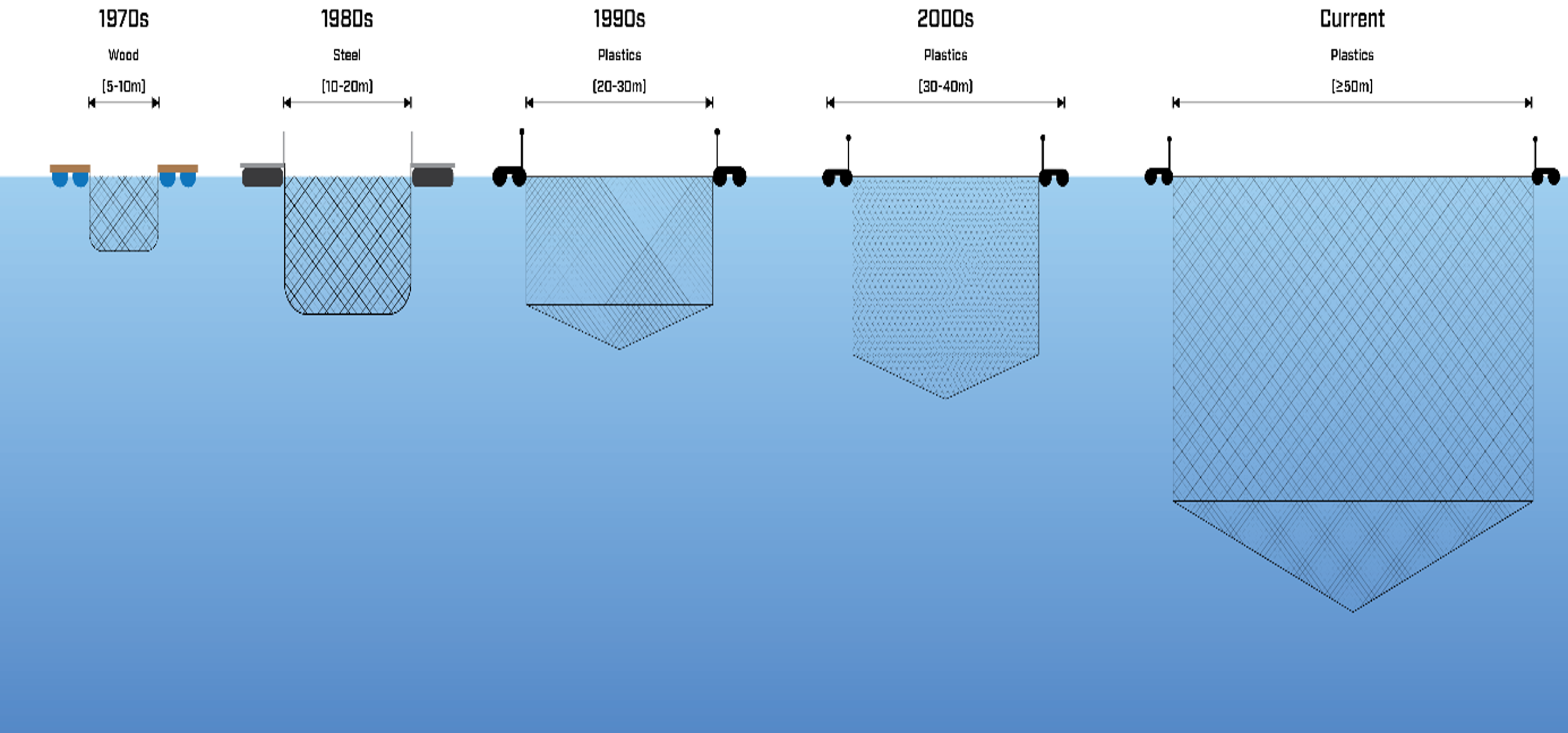

This transformation is visible in the infrastructure itself. Over the past five decades, fish cages have undergone significant expansion in terms of size, depth, and materials. Early wooden structures from the 1970s held modest volumes and operated nearshore. Today, large offshore cages made of engineered plastics exceed 50 meters in diameter and can hold hundreds of thousands of fish (see Figure 3).

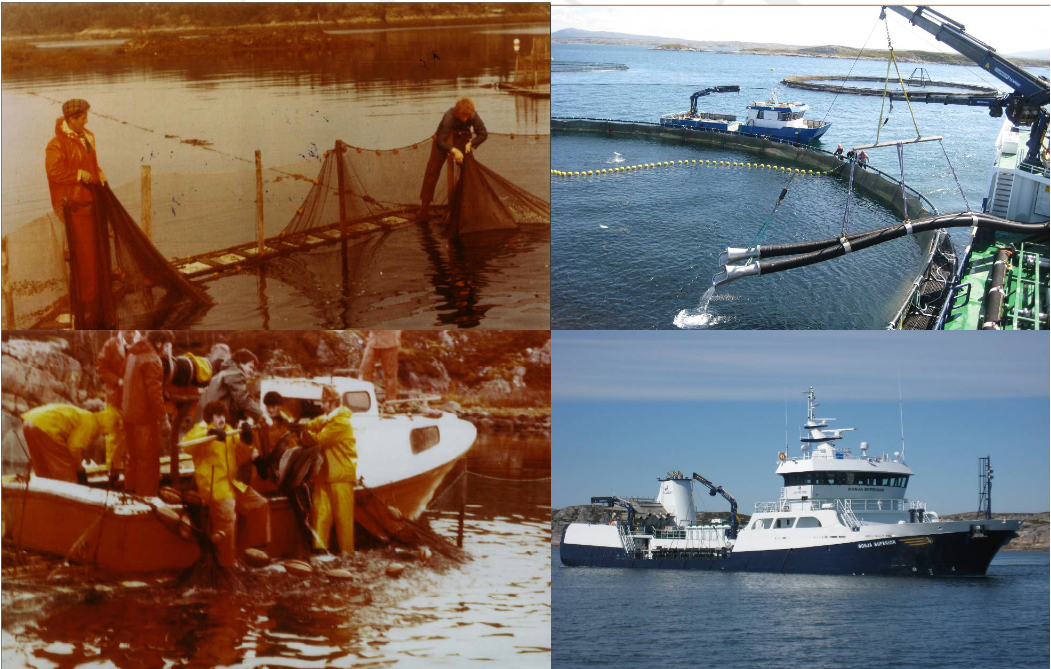

Operationally, aquaculture has followed a similar path of mechanization and specialization. In the past, net handling, grading, and feeding required teams of workers operating in small boats. Today, many of these tasks are handled by specialized vessels and automated systems. The contrast in labor and equipment over time is illustrated starkly in Figure 4.

Like industrial agriculture, modern aquaculture represents a form of controlled production that substitutes capital and infrastructure for space and ecological variability. It is another example of how efficiency gains have reshaped how we produce food, whether on land or at sea.

Please don’t rush to find the downsides of this successful story before you’ve fully considered its merits. Of course, there are many issues, and in this post, we will not discuss the food distribution problem, the exposure of small production systems to global and integrated markets, which means the price does not accurately reflect the fragility of those small ecosystems, etc. Instead, we will now turn to the fiction part of this post, and later, I will try to merge these two to create opinion fiction.

Another fact

Yet as food production has intensified, our diets have become more uniform. In Crops and Man, Jack Harlan warned that modern agriculture was feeding more people with fewer species of crops. Writing in the 1970s, he noted that, of the thousands of plant species historically used for food, only a few dozen had become globally dominant (Stalker, Warburton, and Harlan 2021).

Decades later, Khoury and colleagues demonstrate that between 1961 and 2009, the composition of national food supplies worldwide became significantly more similar. Their study found that the average number of major food crops in national diets rose (from 50 to 60 species per country), but at the same time, the global convergence around a core group of crops increased dramatically (Khoury et al. 2014). Wheat, rice, maize, sugar, and soybeans now form the backbone of most diets worldwide. For example, the share of calories from just these top crops increased in nearly every region, while many regionally distinct crops saw declines. In effect, we are all drawing our calories from the same shrinking global menu (even if that menu includes slightly more items per country than before).

The fiction opinion

Consider that this successful story arises from our ability to domesticate species that are more prone to domestication. Of course, we can comment on every single sentence because the assumption invites us to do so, but I will refrain for the sake of the post’s length and the fact that the reader’s attention diminishes sharply. So, it’s not a stretch to imagine that domestication itself drives this pattern. We don’t attempt to farm apex predators, such as tuna, or massive marine mammals like whales. Instead, we domesticate species that are biologically manageable, socially acceptable, and economically viable, like salmon or trout. It’s also reasonable to assume that profitability has guided our focus, resulting in a reduction of the species we raise and eat compared to what earlier food systems once relied on. Maybe domestication and profitability are two sides of the same coin.

That set of species may still change over time, but the signals driving those changes are now economic more than ecological or cultural. Relative prices1 push producers to reallocate attention toward the most rewarding species. As economists love to say, we’re always choosing the “optimal” bundle. But maybe what’s optimal for production isn’t optimal for diversity… or resilience of our food systems.

1 Relative prices refer to the price of one good compared to another. For example, if wheat becomes more expensive than corn, producers may shift toward corn production. What’s “optimal” changes as these relationships shift.

Perhaps it’s this very combination, i.e., ease of domestication and economic profitability, that underpins the success of food production we celebrate. But there’s something grim hidden in that success. What if the pattern we’re seeing is not simply a deliberate choice, but rather the consequence of many small decisions accumulating over time, each one logical and profitable on its own, yet collectively locking us into a path that’s increasingly difficult to reverse?

This is what economists call path dependence: early choices shape future possibilities, narrowing our options as we go. By selecting species that were easiest to domesticate and produced the highest immediate returns, we created a highly efficient, but increasingly rigid system. Each productive step forward made it harder to diversify or to revert to older, more varied agricultural systems.

Unlike a factory that can retool or machines that can be rebuilt, biological diversity, once lost, isn’t easily restored. Every incremental step toward fewer species and greater productivity tightens our reliance on a smaller genetic base. We’re living off the productivity “dividends,” but at the hidden cost of resilience and adaptability. Over time, the cumulative effect is an agricultural system locked into fewer species, fewer genetic options, and fewer alternatives if something goes wrong.

We didn’t consciously trade away future flexibility; rather, we became locked into this narrow path precisely because it seemed optimal at each step. And now the momentum of past success makes it harder, not easier, to diversify or shift course.

Increasing efficiency has clear metrics, immediate returns, and builds on existing infrastructure. Increasing diversity means starting from scratch with unfamiliar species, uncertain yields, and no established markets. The incentive structure makes the efficient path almost inevitable, even when we know it’s risky.