While the “publish or perish” culture helps individual academics advance their careers through frequent publishing, it creates negative externalities by depleting crucial common-pool resources - especially scholarly attention and peer review capacity. The flood of publications overwhelms the academic ecosystem, making it harder to identify valuable contributions and maintain research quality. This suggests the need for systemic solutions, possibly including novel approaches like Individual Research Quotas, though implementing such measures requires carefully balancing research quality with equitable access to academic publishing.

Overpublishing in academia

I have often felt overwhelmed by the rapid pace of publications in certain fields. As many academics are well aware, there is a reason for this: overpublishing.

Overpublishing occurs when researchers, driven by the pressures of the “publish or perish” culture, prioritize quantity over quality in their scholarly outputs. This often involves fragmenting research into smaller, publishable units (“salami slicing”) or producing studies with limited scientific contribution simply to maintain a steady publication record.

While this strategy may benefit individual researchers seeking career advancement, it comes at a cost.

In this post, I will argue that overpublishing generates negative externalities that distort the research ecosystem (Bellemare 2025; Akbashev and Kalinin 2023). Moreover, I will explore how this phenomenon resembles a common-pool resource (CPR) problem, where unrestricted access leads to congestion and inefficiencies. So bear with me as we unpack this issue.

The publish-or-perish model

The publish-or-perish system emerged from a productivity-based evaluation model, where academic success became increasingly tied to publication volume rather than research quality or impact (De Rond and Miller 2005). This shift has fundamentally altered faculty behavior, making career survival more dependent on frequent publication than on substantive intellectual contributions. However, the implications of this system are multifaceted.

Bellemare (2025) suggests that frequent publishing can enhance scholarly impact through two key mechanisms:

- Probabilistic effects: The more one publishes, the higher the chance of producing a highly cited paper.

- Citation spillovers: Authors who publish frequently tend to be cited more across their body of work.

While high-output researchers are more likely to produce highly cited work, this does not necessarily translate into optimal outcomes for the broader academic community.

Evidence indicates that high-output researchers are more likely to produce highly cited work, suggesting that productivity and impact can be complementary rather than mutually exclusive (Sandström and Besselaar 2016).

The externalities of overpublishing

The publish-or-perish model incentivizes maximizing publication counts at the expense of research depth and cumulative knowledge-building. This creates an overpublication externality, where an expanding volume of fragmented, low-impact studies:

- Overwhelms scholarly attention.

- Creates informational congestion, making it harder to identify and build upon significant contributions.

- Weakens peer review and exacerbates literature saturation.

At the systemic level, an academic landscape optimized for volume rather than intellectual rigor stifles transformative discovery, fuels burnout and redundancy, and fragments disciplines (De Rond and Miller 2005; Akbashev and Kalinin 2023). In this way, the drive for publication distorts knowledge production and degrades the mechanisms meant to ensure its quality.

While high publication output is individually rational, it generates collective inefficiencies that undermine long-term scientific progress. This is the hallmark of a common-pool resource problem, where unrestricted access leads to overuse and depletion.

Scholarly attention as a CPR

Overpublishing clearly functions as a negative externality within the academic ecosystem, and it does so in large part by overtaxing a critical common-pool resource: scholarly attention.

Although various CPRs (e.g., peer reviewer availability, editorial capacity, research funding, and public trust) are affected by excessive publication, the most directly strained resource is the finite time and attention of the research community. When researchers collectively produce an overabundance of fragmented or low-impact studies, it becomes increasingly difficult for audiences to identify, absorb, and build upon important work. This congestion diminishes overall research quality and hinders cumulative scientific progress, underscoring the need to view overpublishing through the lens of CPR depletion.

What if we introduced Individual Research Quotas?

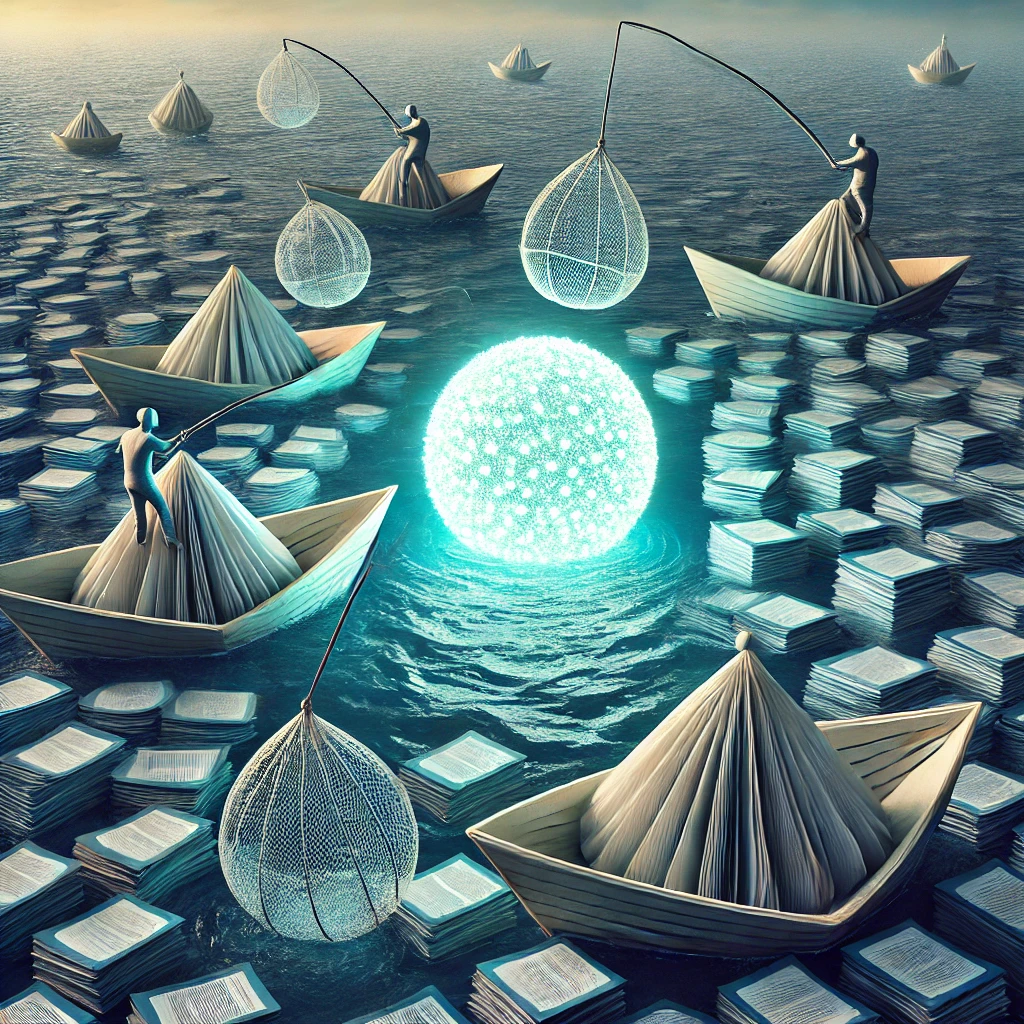

Given this framework, what if we designed a system akin to Individual Fishing Quotas (IFQs)… an Individual Research Quota (IRQ)?

IFQs slow the race to fish, reduce overcapitalization, improve safety, and extend fishing seasons by recognizing that access to a resource is not unlimited (Birkenbach, Kaczan, and Smith 2017).

What if we applied the same principle to academic publishing? What if publication were not an unrestricted right but a regulated privilege, allocated deliberately to prevent the exhaustion of scholarly attention, peer review capacity, and editorial resources? Could such a system shift incentives away from sheer volume and toward deeper, more meaningful contributions?

Yet, the real challenge is not just whether such a system could curb overpublishing, but how it could do so without reinforcing academic elitism or concentrating research power in the hands of a few.

Would an IRQ system democratize knowledge production, or would it risk restricting access even further? If we can regulate fisheries to ensure sustainability, can we regulate knowledge production in a way that preserves both quality and equity?

IRQ is just one of many possible policy solutions. There are likely many other approaches that could emerge within this framework. IRQ is on top of my head by professional deformation.